Lives in history of the Mediterranean: Martin Lings

The second installment of the series curated by Pietrangelo Buttafuoco tells the story of Martin Lings

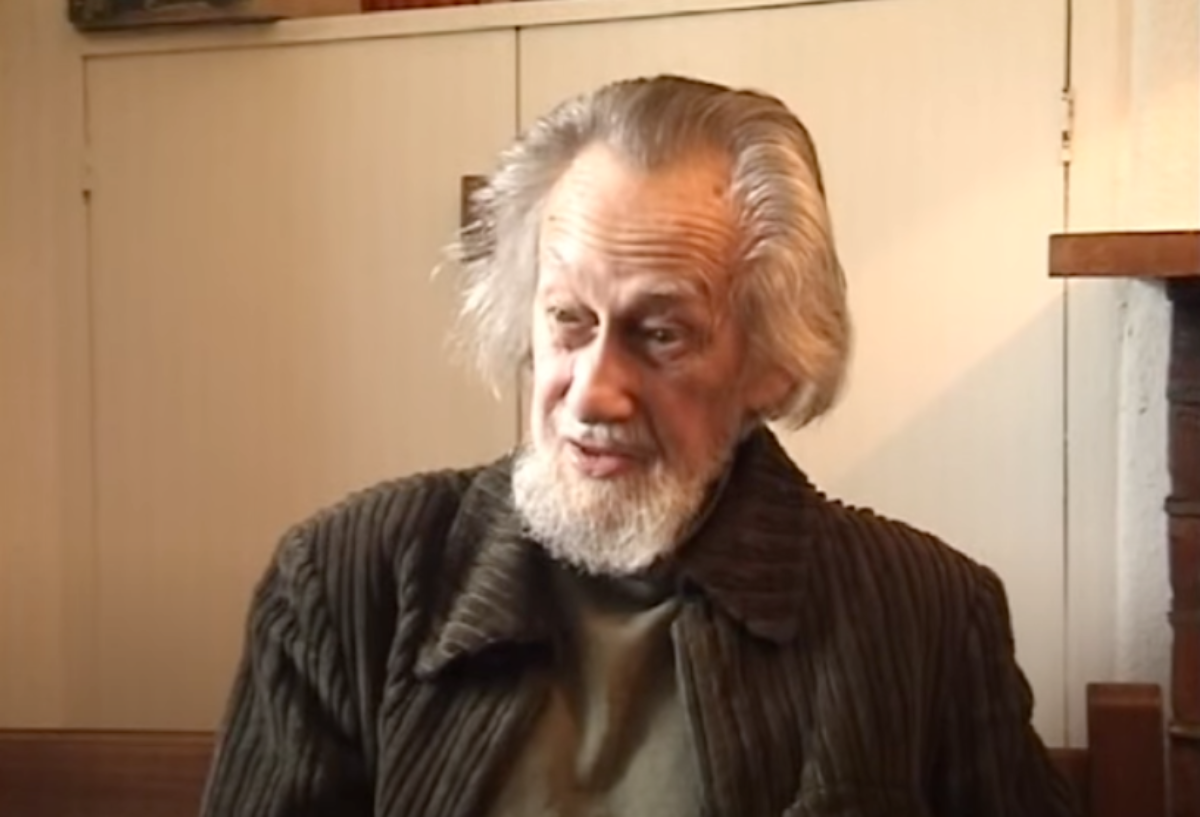

Martin Lings was just as at ease in his unbuttoned, exquisitely tailored, very British corduroy jacket at his home in Westerham, Kent, as he was throwing a bisht, the traditional Arab cloak woven out of camel’s hair and goat wool, over his shoulder in the streets of Cairo.

Like water can change its form, he could be a librarian, a Sufi or a professor. He was so devoted to Frithjof Schuon, the closest among his teachers, that he ended up resembling him in many ways – same gaze, same gait. As every true disciple is destined to do, Martin ended up surpassing him.

While Schuon expressed himself through his tireless German complexity, Lings described the Prophet with turgid language. And while Schuon is remembered for a perennialist mysticism that bordered syncretism, the form of Sufism Lings brought to the West was much less cryptic.

Lings’ clarity and rigour came from his incessant studies on Shakespeare, whose works he got to know by way of C.S. Lewis, the most influential figure in his education. Struck by Shakespeare in his youth, Lings read English at Oxford. There, he stood out among Lewis’s students and befriended him in just a few months. If Lewis became his cultural master, Shakespeare became his spiritual guide - the first of many to come.

As he arrived in Cairo, Lings converted to Islam. He named himself Abu Bakr, after Prophet Muhammad’s best friend and first Caliph of Islam, and took upon himself the obligations of fasting, praying and remembrance. He learned each practice step by step from the Egyptian branch of the Shadhili brotherhood, a religious order founded in Morocco in the 13th century, widely present in North Africa. The presence of French Philosopher and writer René Guenon in Cairo in those years gave the order new lifeblood – and that influence is still being felt today.

While Lings was looking at Shakespeare for inspiration for a new European spirituality, Guenon conquered his young French followers with his analyses on Taoism, Hinduism and even Dante (see “The esoterism of Dante”), which he considered to be different streams of one single universal tradition.

Guenon, Lings and Schuon all converted to Islam and looked for a way to revive the Western world through a cultural effort which never meant recantation.

In Cairo, Lings soon became an English Literature lecturer at the University. As fate would have it, the death of his predecessor had left the position vacant and, in the ensuing chaos, he was the only candidate available to take it up.

His Egyptian students expected something different. They had become used to proud, distant Brits, willing to keep their teachings to a minimum - so that they could maintain their superiority - and determined to flash before their students’ eyes a culture, locked up within books, that would remain impenetrable to them.

Lings’ teaching style, instead, is based on the assumption that literature comes alive when it is put on stage, when it stops just living in the pages of a book and is etched out in people’s memories and gestures. And so, for the first time, Shakespeare’s work was performed at Cairo University. Every year, Lings chose a play and worked with a group of students – some of whom would end up becoming famous Egyptian actors – creating costumes, working on the scenography, and finally, happily taking a seat to watch the show.

We can imagine what his afternoons were like: after a rehearsal of Othello – his favourite among Shakespeare’s works since his younger days – he would join his brothers for the hadra, the traditional chant that becomes a prayer.

Lings was the living antidote to the clash of civilisations, to the idea that converting to a different religion meant taking sides with a whole culture, that becoming a Muslim would mean relinquishing one’s Western cultural background.

It is impossible to think Lings’ conversion process followed a linear pathway, with a “before” and an “after” along the lines of St Paul’s conversion on the road to Damascus. On the contrary, the quiet Shadhili spirituality pushed him to go back to his origins, again and again. Lings’ own secret is unveiled in the subtitle to his book “The Secret of Shakepeare”, published 40 years after his arrival in Cairo: “His Greatest Plays Seen in the Light of Sacred Art”.

To Lings, Shakespeare’s greatness becomes evident when his works come to life. Only when they are put on stage can you get a taste of the mystery of sanctification. It is not a simple question of phenomenological observation. As Lings clearly stresses in the chapter on Macbeth: “the presence of the soul cannot be constrained in mere esoteric considerations”.

And as he attempted to delve deeper into the Bard’s most mysterious plays, Lings availed himself of Islamic symbols, as Guenon also did. Now, decades after his first infatuation with Othello, Lings could finally explain where it came from: “the soul, personified by the Moor, gradually plumbs the very depths of error, that is, of thinking that black is white and white is black, that falsehood is truth and truth falsehood.”

Through Lings’ work we can easily visualise the story of an ambitious young man, constrained by the colour of his skin and his religious faith, who pretends to change to avoid being marginalised. This is the theory that inspired one of the last performances of Othello by the English Touring Theatre.

Sacred art is a keyword which almost acquires a magical meaning in Lings’ imagination. Schuon himself had worked on the enigma of art, on how it transitioned from the sacred to the profane in the universal tradition (“Art from Sacred to Profane: East and West”) and how it hinged on universal symbols, as René Guenon had taught them both in his “Symbols of Sacred Science”.

In the last decades of his life, Lings devoted himself to art. He returned to London to work as librarian, taking care of oriental books and manuscripts at the British Museum. He collaborated with the British Library and, in the space of a few years, organised the most important event on Islamic Art that ever took place in the West: the World of Islam Festival in 1976. The publications produced for this event are authentic gems for their contents and artwork.

Martin Lings’ works live on in Italy too. His meticulous work Muhammad: His Life Based on the Earliest Sources (published in Italy in 2004) is the most popular biography of the Prophet among Italian Muslims. Its narrative is delicate, as is the description of characters – in stark contrast with the cold approach one would expect of an essay.

For Lings, Islamic culture had to be a living thing. He had already understood this as he was pursuing his Doctorate, when he wrote his thesis on Ahmad al-‘Alawi. Entitled “A Sufi Saint of the Twentieth Century”, the book gives a vertiginous description of al-‘Alawi from all perspectives simultaneously. It alternates biography and interviews, translations and lyricism, with a tri-dimensional frenzy that pursues a sole purpose: showing that sanctity has always been present in history, and that at any given time there are elements, albeit often hidden, to show it.

In his old age – he died at 96 – Martin Lings collected books, travelled extensively, organised exhibitions and took care of his house. He became increasingly obsessed with the symbolism of colours – an interest that had been shared by all his masters. His obituary in the Guardian, penned by Gai Eaton, bears testimony to this with a detailed description of Lings’ long search for a peculiar shade of blue that reflected celestial perfection.

Surrounded by the most perfect blue, Lings absorbed its mysterious properties, and was privileged to die a peaceful death.

The secret of Lings and the secret of Shakespeare are what we need today. His path is not to be followed by esotericists, but by those who believe that the Western world is not destined to die. It is for those who want to contradict both Spengler’s theory of the decline – or sunset – of the West and Houllebecq’s views on euthanasia.

Lings’ final message of hope is channelled through his book “The Eleventh Hour”. His analysis of the spiritual crisis of the modern world and his belief that the end is in sight, but not yet imminent, are re-interpreted in the light of the parable of the vineyard workers (Matthew, 20: 1-16), in which the workers who were hired late in the day were paid as much as those who had been hired earlier. To Lings, this message echoed the hadith in which God states: “My mercy overcomes my wrath”.

In the final hour, in darkness and oblivion, mercy abounds. And so do people like Lings, who countered a conflict narrative that pitched the West against Islam, and were ready to re-discover their own spiritual tradition using everything they found to shine a light.

Massimo Campanini (1954-2020) is one example of this. Albeit sceptical about Lings’ religious approach – which leaned too much towards Sufism for his taste – he studiously followed his footsteps. While sympathising with the most rationalist current in Islam theology, the neo-Mu’tazilah, in the last years of his life he found himself – just like Lings – writing a biography of the Prophet starting from scratch, leaving behind all the dogmas accumulated by experts in Arab and Islamic studies up to that point (“Maometto”, 2020). He also unveiled Dante’s Arab-Islamic mysteries (“Dante e l’Islam”, 2019) in the hope that this would put an end to the “oblivion of Islam in the Western world”.