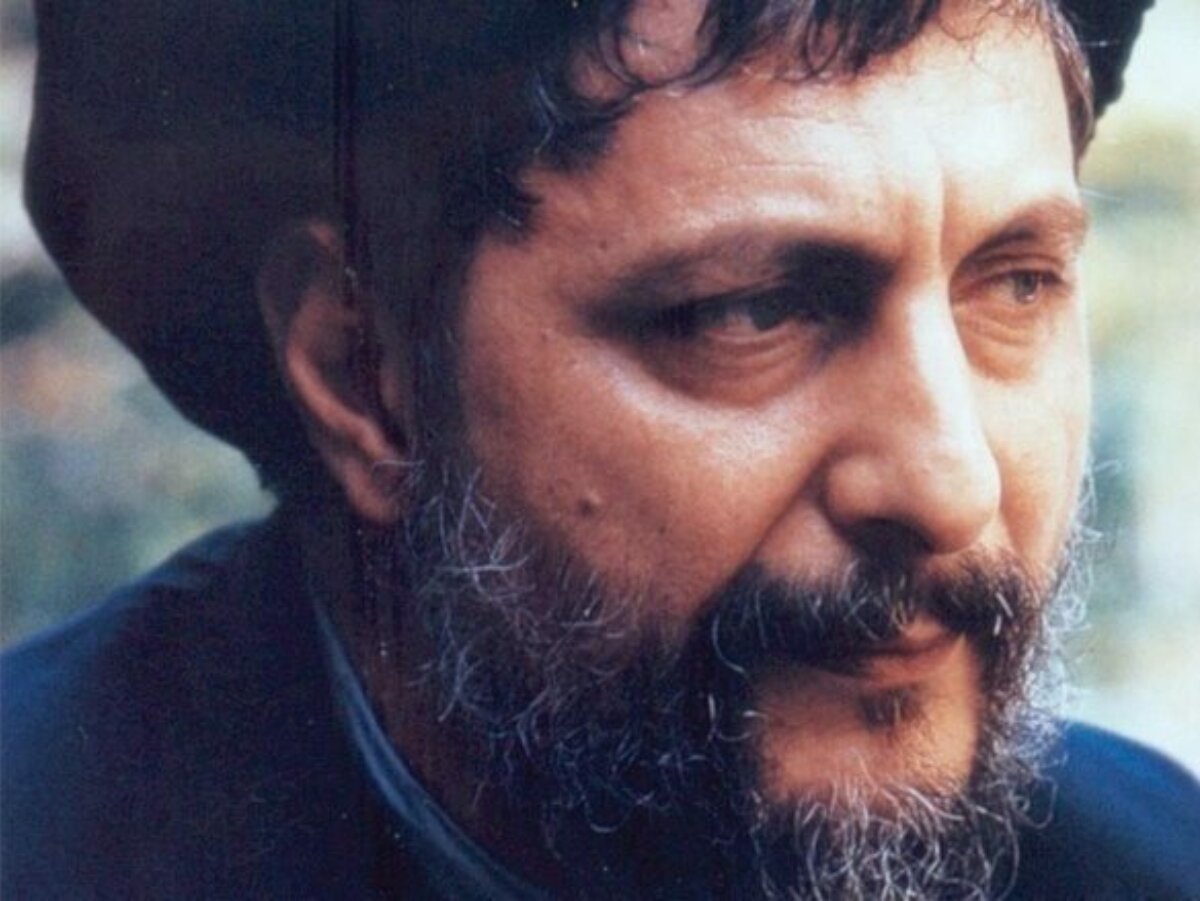

Lives in the history of the Mediterranean: Musa Sadr

The first installment of the series curated by Pietrangelo Buttafuoco tells the story of Musa Sadr, one of the leading figures in the intellectual renaissance of Shia Islam, which is present – in its complex articulations – in many countries across the Near East.

Imam Musa Sadr was born in Iran on 4 June 1928, into an important religious family of Lebanese origins. Educated in Qom, Tehran and Najaf, he was undisputedly one of the leading figures of public life in Lebanon and more broadly in the Islamic world. He is also considered one of the leaders of the intellectual renaissance of Shia Islam in the second half of the 20th century. He disappeared on 31 August 1978 in Libya, in mysterious circumstances.

His biography holds the key to a deeper understanding of his thinking. Like many Shia clerics, he travelled and lived between Iran, Iraq and Lebanon. In doing so, he appeared to reject contemporary political boundaries, identifying instead with a broader spiritual geography, reminiscent of the power of Islam in medieval times, when great historians, philosophers and jurists used to wander among the many spiritual capitals of the Near East, learning and teaching.

As is often the case with members of Ahl al-Bayt families who trace their origins back to the Prophet, Sadr felt at ease in both the Persian and Arabic speaking worlds.

After acquiring his first certification in Islamic law (darajāt al-ijtihād) in Qom, in 1950 he enrolled at the University of Tehran – a truly revolutionary decision for the times – where he graduated in Economics in 1953. Having proved his worth outside the safe environment of the seminary, in 1954 he moved to Najaf, in Iraq, where he lived until 1958. There, he successfully continued his studies and came into contact with the main Shia clerics in the city, whose religious seminars rivalled Qom’s for prestige.

During those years, Sadr travelled to Lebanon twice, visiting the part of his family living in that country. There, he made contact with Abd al-Husayn Sharaf al-Din al-Musawi, the leader of the Lebanese Shia Muslims, whom he would later replace. It is not uncommon for Iranian Shia clerics to have Lebanese origins, as Lebanese clerics had been brought into Iran by the Safavid dynasty to convert the country – still largely Sunni at the time – to Shi’ism.

In 1959, Musa Sadr finally moved to Lebanon and started re-organising and building the local Shia community. This work would lead to the foundation of the Amal Movement and to the gradual political empowerment of the Shias, who had been politically underrepresented for a long time. This would in turn enable them to play a major role in the multi-faceted political landscape of Lebanon – a country described by Lebanese historian Kamal Salibi as 'a house of many mansions'.

Thanks to his passion, compassion, political foresight and religious charisma, Musa Sadr soon became the most important religious leader of the Lebanese Shia. In 1969, he was chosen as Head of the Supreme Islamic Shia Council, an official entity meant to give the Shia a bigger say in political decisions. However, his position on political Islam was different from that of Ruhollah Khomeini, the other great protagonist of those years.

In contrast with Khomeini, Sadr did not believe in the velayat-e faqih, or guardianship of the Islamic jurist, which would become the cornerstone of Iranian politics after the 1979 revolution. His vision was aligned with that of some of his contemporary marjaʿal-taqlīd, such as Sayiid Hossein Tabataba’i Borujerdi and Mohsen Tabataba’i Hakim, whom he represented in Lebanon. According to information posted on the Imam Sadr Foundation's website, between 1962 and 1978, Musa Sadr created several centres, initiatives and institutes to increase cohesion in the Lebanese Shia community.

This is in line with Islamic tradition and with the strategy of many movements, including radical ones, which used social assistance as a basis on which to build political consensus. Musa Sadr started his activities in the poorest neighbourhoods of Tyre – the city his family hailed from – where he promoted programmes to support and provide aid to the needy and to local communities.

His work included literacy programmes and the creation of religious institutions focusing on the promotion of social integration, with a special emphasis on the role of women in the economy. Although the environment in which these activities were developed was still somewhat conservative, the impetus Musa Sadr gave them was such that it made him a reference for all those who believe that Islam can acquire aspects of modernity without losing its own identity.

Musa Sadr’s disappearance on 31 August 1978 in Libya, where he had travelled upon Muammar Gaddafi’s invitation, remains one of the most complex mysteries in Near East politics in the last decades. Although experts tend to agree on blaming his disappearance on the Libyan leader, who supposedly ordered his assassination, Gaddafi always rejected these allegations, claiming that Musa Sadr and his companions had regularly left Libya and headed to Italy.

Sadr’s family, on the contrary, has always maintained that the Imam was imprisoned by Gaddafi. Based on this conviction, when the Libyan regime collapsed in 2011, both Lebanon and Iran multiplied efforts to ascertain the Imam’s fate and whereabouts.

In any event, Sadr’s disappearance just before the start of the Iranian revolution, at a time when tensions ran high between Lebanese Shias and the Palestinians led by Yasser Arafat, created a vacuum in the Near East’s political and ideological landscape. On the one hand, this weakened Lebanese Shias and, on the other, it strengthened those who saw the rise of an Islamic Republic as the only possible avenue to put clerics back in power.

However, I believe it is useful to expand our analysis beyond mere politics, to include elements of Musa Sadr's approach as leader of the Shia community. He strongly believed that it was both opportune and necessary to enable people to understand and meet their own needs, restoring the dignity of those who had long been treated as ‘children of a lesser God’.

In his vision, this applied to men and women alike – a crucial detail in both rural and urban communities in the Near East, where the emancipation of women is a revolutionary concept in itself. The progress deriving from this strengthens participation, dialogue and the acknowledgement that ‘the others’ also have their rightful claims – and this, in turn, creates a conducive environment for lasting peace and continuing cooperation between different communities. This applies to family life and local activities, as well as to the relations between religious denominations, nations and peoples. Sadr wanted Lebanon to be the living proof of the validity of his belief that economic, social and political justice is a key element for the virtuous coexistence of different entities. While his dream remains difficult to achieve, it has inspired the actions of his followers and of the Foundation that bears his name, showing that an alternative vision for the future is possible.

The core of Musa Sadr's thinking lies in his religious vision, which inspired constant efforts to promote cohabitation and tolerance between different religious groups. In 1963, he participated in the coronation of Pope Paul VI. This was around the time of the Second Vatican Council, which had a strong influence on Sadr. The fact that he was the only Muslim dignitary to be officially invited to the ceremony bears testimony to his closeness to the Catholic Church. He was a staunch promoter of religious dialogue and of the coexistence of different faiths in Lebanon, as testified by the following closing statement to a sermon he held in Beirut’s Franciscan Church on 18 February 1975:

“…Oh, ye believers, men and women, let's find a common ground in the humanity each of us shares. Our words and actions must concern each and every person: those in Beirut, those in the South, those in Hermel, those in the Akkar, and those in the outskirts of the capital, from Karantina to Hayy El Sullum. Nobody must be excluded, marginalised or singled out. Let us defend Lebanon’s human beings to defend this country, a country made of human beings – a pledge from history and pledge from God.”

A book recently published in Italy, 'Religions at the service of the human being', which contains a collection of Musa Sadr’s speeches and writings, shows how, for him, the human being always took centre stage, because, in his words “all the energy of the human being – of all human beings – must be preserved and developed”.

This focus on the human being is justified by Sadr’s view of the relation between the human being, the world and God. In the same sermon he stated:

“There used to be one religion, because the genesis – God – is one, and the goal – the human being – is one, and the way – God's creation – is [also] one. When we forgot the goal and we distanced ourselves from the service of the human being, we forgot God and He distanced Himself from us.

“We split into groups (firaq) and evil was thrown among us. Therefore, we found ourselves in disagreement, breaking up God's creation, serving sectarian interests, adoring divinities other than God.

“In doing so, we wore out the human being, who eventually got torn apart. Let’s go back to the Way, now. Let's go back to the human being, so that God will come back to us. Let's go back to the human being, afflicted by torment, so that we can save ourselves from the torment (al-‘adāb) of God. Let's come together around the human being – oppressed, worn out and torn apart – so that we can come together in every thing, and, in doing so, come together in God, and religions will be one.”

To conclude, the following excerpt from a speech given by Sadr on 30 May 1966, a week after the assassination of journalist Kamel Mrowa, illustrates the importance of freedom and dignity in his view:

“As for freedom, brothers, you know it is the best tool to mobilise all the energy of the human being: the service provided by the human being – any human being – in a society that is not governed by freedom, only amounts to a part of his energy, not all of it. The human being cannot mobilise all his energy and develop his talents unless he is granted freedom. Freedom is the best instrument to invest in the energy of the human being and to put all of it at the service of society.”