Beyond the Axis: the Houthis and the strategic diversification of alliances

Through the visibility and the popularity of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden attacks, the group is intensifying contacts with Russia and other terrorist groups in Africa and the Middle East. An analysis by Eleonora Ardemagni

Following the events of October 7, the Yemeni Houthis (also known as Ansar Allah “Partisans of God”), have further strengthened their political and military alignment with the so-called Axis of Resistance, a coalition led by Iran. Despite this increased integration, the Houthis remain the most autonomous entity within the alliance. In both rhetoric and action, the leadership of the Houthis is consistently remarking their affiliation with the Axis.

On the night of Iran’s first direct attack on Israeli territory, on April 13, the Houthis launched drones toward Israel (as also Hezbollah did), which were subsequently intercepted. Later, on July 19, the Houthis successfully struck central Tel Aviv with a drone, resulting in a fatality. In response, Israel retaliated on July 20 by targeting the Yemeni port of Hodeida, under Houthi control. The Houthis also participated in meetings organized by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (Pasdaran) in Tehran, following the burials of Ebrahim Raisi and Ismail Haniyeh.

Despite their growing closeness to Tehran, the Houthis are simultaneously forging new partnerships and alliances both within and beyond the Middle East. These emerging relationships, while aligned with pro-Iranian and anti-Western sentiments, differ from the previously dominant Iran-Hezbollah backbone that has largely defined Houthi foreign policy in the region.

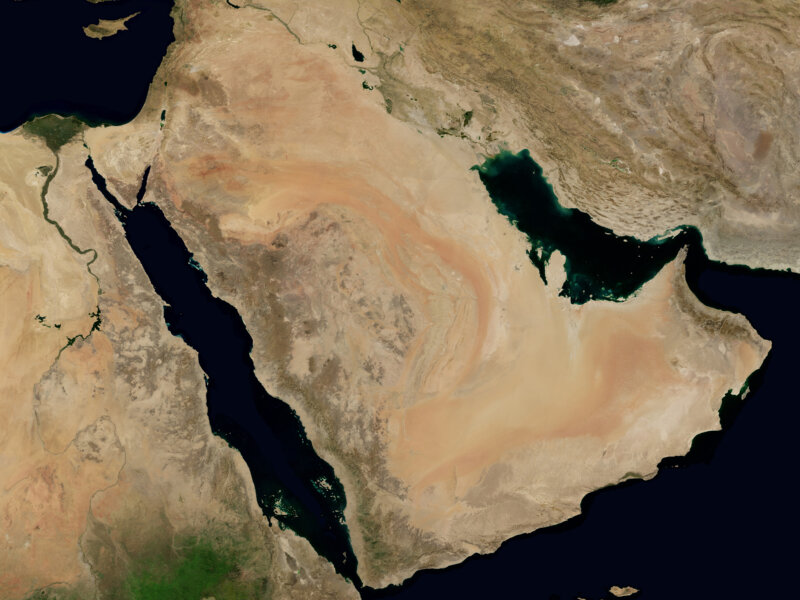

Since 2024, the Zaidi Shia militia movement in northern Yemen has significantly increased its interactions with Shia Islamic Resistance militias in Iraq, the al-Qaeda-affiliated Shabaab in Somalia, and Russia, exploiting the visibility and, to some extent, the popularity gained through attacks on commercial shipping in the southern Red Sea, the Bab el-Mandeb, and the Gulf of Aden.

These emerging forms of cooperation point to three key objectives currently pursued by the Houthis. The first is to expand the geographical scope of their alliances beyond the Middle East to include the Horn of Africa and other extra-regional powers. Such an expansion would enable the Saada-based movement to project its influence towards the Mediterranean and the western Indian Ocean. By doing so, the Houthis could potentially influence – directly or indirectly, through a network of alliances – a broader region, also by a commercial standpoint.

The second is to secure multiple arms supply channels beyond Iran and, prospectively, new revenues to finance the war in Yemen and beyond. Diversification may have the primarily practical reason to prevent the Houthis’ arsenals from “keeping up the pace” of the Red Sea offensive. All this should be merged by the militarization of the front lines in Yemen if the now expired truce breaks down. In April, General Alexus Grynkewich, commander of the US Air Force in the Middle East, stated that the Houthis might be running out of drones and anti-ship missiles. Such a hypothesis comes back to the surface every time the group slows down its attacks on shipping but it downgrades when the frequency of attacks increases again.

The third objective, the most strategic, is to increase the movement's autonomy. Indeed, the priority for the Houthi leadership is to keep their “hands free” from Iran and the Axis. And this is becoming even more important now that the Houthis continue to integrate themselves with pro-Iranian armed groups.

The U.S. is convinced that the Houthis have already begun to diversify in supplying weapons. On August 7, during a webinar organized by the U.S. think-tank Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), Vice Admiral George M. Wikoff, Commander of U.S. Naval Forces Central Command (NAVCENT), which includes the Fifth Fleet in Bahrain and the Combined Maritime Forces, argued that “the Iranians are certainly supporting the Houthis, but the Houthis are diversifying”, not least because “we don’t think the [arms] supply is necessarily limited to the Iranians”.

Islamic Resistance in Iraq

In May, the Houthis announced their coordination of military operations with the Islamic Resistance in Iraq (IRI). The IRI is a banner that emerged after October 7 and is used by Iraqi Shia militias closely aligned with Iran, including Kataeb Hezbollah, to claim responsibility for attacks on military bases housing U.S. soldiers in Iraq and Syria. Both the Houthis and the IRI have claimed involvement in several joint operations targeting merchant ships in the Mediterranean, particularly near the Israeli port of Haifa; however, none of these attacks have been confirmed by either Israel or the U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM).

Investigations by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) suggest that the Houthi drone that struck Tel Aviv on July 19 (which took the “long” route, flying over the Red Sea, Eritrea, Sudan, and Egypt) was not intercepted because Israeli radar operators were simultaneously tracking another drone launched from Iraq, which was subsequently shot down. This may indicate further signs of coordination between the Houthis and Iraqi groups.

The Iraqi militias, who claim their attacks with the mark “IRI”, are part of the Popular Mobilization Forces. They are therefore part of the Iranian-led Axis of Resistance. However, the Houthis directly manage cooperation with the IRI, albeit with Tehran’s approval: since 2015, leader Abdelmalek Al Houthi has appointed a personal representative in Baghdad. For the Yemeni group, strengthening ties with the Iraqi Shia militias is also a strategic step toward the beginning of the “fourth phase of escalation” in the Red Sea. According to the Houthis, this phase involves more attacks on shipping routes to the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean.

The Shabaab in Somalia

According to the theory leaked by US intelligence last June, in Somalia the Houthis are said to be colluding with the Shabaab to supply them with weapons and in particular drones, although there is no evidence of this agreement yet. Al-Shabaab, a Sunni terrorist organization affiliated with al-Qaeda, also receives military support from Iran. The agreement with the Somali group would provide the Houthis with additional profits to finance the war – through a different but convergent channel from Iran – and would allow them to cultivate their ambitions to strike in the western Indian Ocean, thanks to their new partners.

As early as 2021, a report by the Global Initiative Against Organized Crime (GITOC) highlighted the arms connection between Yemen and Somalia, noting that some of the weapons used by al-Shabaab came from shipments sent by Iran to the Houthis. In 2023, the final report of the UN Panel of Experts on Yemen noted “the existence of a closely coordinated network operating between Yemen and Somalia, which receives weapons from a common source”, identified as Iran.

Russia’s role

In 2024, relations between the Houthis and Russia have intensified. Russian military intelligence officers have been deployed in Houthi-held territory for “several months”, according to U.S. intelligence. Their objectives may range from providing training in the use of weapons to identifying commercial targets for anti-Western operations. It has been reported that President Vladimir Putin considered supplying the Houthis with anti-ship missiles but although he has thus far refrained from doing so under pressure from Saudi Arabia: a hypothesis that has alarmed the United States.

Moscow’s position of apparent neutrality in the Yemen conflict has not formally changed. However, its interactions with the Houthis have become more intense, coinciding with the Red Sea offensive. Since the beginning of the year, a Houthi delegation has made two visits to Russia to meet with Mikhail Bogdanov, the Deputy Foreign Minister responsible for Middle Eastern affairs. Moreover, there was also a meeting in Oman last July. Furthermore, Moscow has also been increasing its contacts with the internationally recognized Yemeni government and has established relations with the Southern Transitional Council, the southern secessionist group.

While Russian-flagged commercial vessels were not directly targeted by the Houthis in the Red Sea, cargo and oil tankers carrying Russian goods, particularly those that had previously docked at Israeli ports, were hit during the offensive. The significant reduction in commercial traffic along the Suez-Bab el-Mandeb maritime route means that the few remaining ships, mostly non-Western, have to face an increased risk of being targeted, including those linked to Russia and China.

Speculation in the media suggests that the Houthis may have reached an agreement with Russia (and potentially China), offering safe transit for commercial vessels in exchange for political support in the UN Security Council. While this remains a hypothetical arrangement, Moscow has abstained from voting on Red Sea resolutions without exercising its veto power.

Possible scenarios

After October 7, the Houthi militia movement entered a new phase. The Yemeni group is becoming increasingly integrated into the so-called Iran-led Axis of Resistance, although it remains the most autonomous component within this alliance. The Houthis’ ability to successfully carry out the 2015 coup was significantly supported by the arms and the assistance of former Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh. Similarly, their uninterrupted continued control over almost half of Yemen's territory after nine years of conflict, which has led Saudi Arabia to engage in negotiations, is largely attributable to the support, arms, and training provided by Iran and Hezbollah.

With the opening of the Red Sea front, the Houthis have expanded their influence beyond the pro-Iranian sphere, utilizing their opposition to Israel and the United States to enhance their visibility and appeal among a broader anti-Western audience. This political strategy aims to gain support across religious and sectarian lines, mirroring the approach adopted by Hezbollah following the 2006 war with Israel. Consequently, the Houthis’ strategic outlook does not imply political and military subordination to Tehran. Rather, their alignment with the Axis of Resistance is accompanied by efforts to forge new partnerships and alliances within the pro-Iranian sphere, with the objective of increasing their geographic, military, and economic capabilities and thereby strengthening their autonomy.

Moreover, the deepening of the Iran-Russia alliance could potentially enable Moscow to extend military support to the Houthis, possibly through indirect channels involving Tehran. The network of new partnerships and alliances that Houthis are developing, both within and beyond the Middle East, represents a dynamic element that requires careful monitoring, as it could further influence regional instability.